Michigan Sugar took over the Owosso plant in about 1928. Soon after the facility was used only as a depot for the local farmers, until the beets could be shipped to the Saginaw plant.

The Owosso plant has not been used to store or process beets since the 1950s.

Sugar Beet Workers circa 1910.

These two photos were taken at the Owosso Fairgrounds and Race Track of Sugar Beet workers

1954

Postmaster Edmund 0. Dewey, uncle of the famous Governor of New York, Thomas E. Dewey, having a wide acquaintance with farmers, business men and financiers, took it upon himself to revive the project a year later. He had underway the task of urging the citizens to vote for an $8,000 bond issue to defray the cost of a site for a new post office building, which the Department agreed to build if the city would supply the site free. He strove to improve the postal facilities as well as the traffic to justify them.

A favorable circumstance was Deweys acquaintance with Joseph Kohn, Kilbys outstanding sugar technclogist. In the previous year Kohn had induced a group of officers and stockholders of the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company to establish the Michigan Chemical Company and to build its distillery in Bay City for the purpose of elaborating the waste molasses from the sugar factories. The great Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co. required potash in its manufacturing process, which the distillery was expected to extract from the slop. Subsequently it developed that the plant could produce no potash but it did produce excessive profits. Accordingly the stockholders gave ear when Kohn submitted a prospectus and urged em-barkation into a sugar venture. Besides the direct profit there was the prospect of control over the supply of the raw material for their distillery.

Dewey dangled before his neighbors in Owosso the plum of an $800,000 capital investment for a factory in the home town and an annual expenditure of an equal amount for beets, labor and materials. For the consideration of the farmers he declared that beet growing was the great farm mortgage lifter. All that was demanded to acquire these benefits was a pledge to grow 8,000 acres of beets for two years and to raise the sum of $20,COO to reimburse the venturers for the cost of the site and certain organizational expenses. The Postmaster urged the voters of the City of Owosso and the County of Shiawassee to authorize a bond issue of $10,000 each and thereby distribute the cost to all of the beneficiaries.

Dewey, unhampered by a sugar committee, could make decisions and act according to his own judgment. Without waiting for the election, he collected $10,000 from civicminded neighbors and by the middle of October, 1902, he had arranged for the purchase of a 40-acre site at the west end of Oliver Street between the Ann Arbor and Michigan Central Railroads. The County Board of Supervisors voted no on the bonds while the city dwellers voted yes, but a citizen obtained an injunction because of alleged unconstitionality.

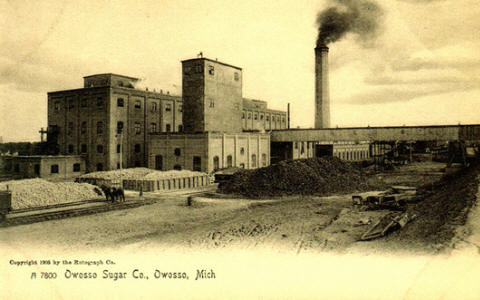

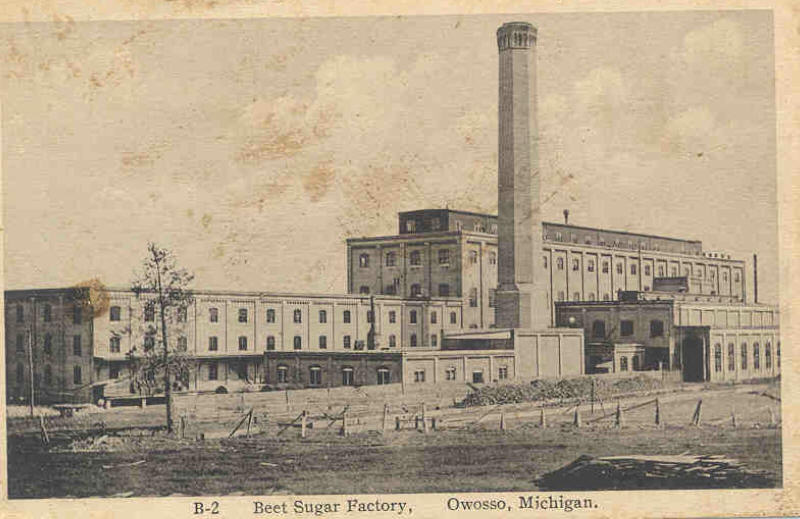

Nevertheless on October 29, 1902, the owners of the Michigan Chemical Company of Bay City incorporated the Owosso Sugar Company with a capital of $1,000,000. There was no formality. The officers of the Chemical Company served in their respective positions in the Sugar Company, to wit: - President, Captain Charles Vt Brown (President of the Pittsburgh Plate Glass Co.); Vice President, Edward Pitcairn; Comptroller. A. Pitcairn, all of Pittsburgh: SecretaryTreasurer and Manager, Carmen Smith of Bay City; Assistant, Bertram E. Smith of Owosso and General Superintendent, Joseph Kohn of Bay City. Captain Brown, the Pitcairns and associates in the Glass Company supplied the funds. Carmen Smith had come from Minneapolis where he practiced law. His friendship with Captain Brown led to his appointment to the managership of the new Michigan project. His choice for this position was a happy one. His outstanding characteristic was his ability to compose ruffled spirits. When disagreements arose in the industry conventions he could always be depended upon to calm the troubled waters with a story that brought good humor to the assembly.

A contract, bearing the same date as the incorporation, was awarded to the Kilby Manufacturing Co. for a 1,000ton factory for a total price of $675,000, exclusive of the foundations. A week later Kilbys civil engineer was on the job to stake out the buildings, design the foundations and obtain the right of way for the sewer. Shortly thereafter he sublet the concrete work to Schillinger Bros. of Detroit and the brick work and carpentry to Sco11 Bros. ($110,750) also of Detroit.

At this time Richard Hoodless of Caro was commissioned to circulate among the farmers and employ his talent for acreage solicitation in cooperation with Agriculturist L. B. Dolsen whose specialty was the art of beet Culture. The farmers did not overflow with enthusiasm. Carmen Smith and Joseph Kohn therefore got the idea of a companyowned farm to supplement the beet supply. It happened that there was a large area known as the Prairie Farm, estimated at 9,000 acres, near Chesaning in Saginaw County between the Shiawassee and Flint Rivers about 28 miles south of Saginaw. This area formed a low basin which annually received the overfiow from the floodswollen creeks and rivers. For years the heavy spring rains and melting snows had washed rich wellfertilized top soil into the rivers and thence into the settling basin. Subsequently the water separated by seepage and evaporation and left a layer of chemurgic wealth. For the small operator who had to extract his livelihood as he went along, or starve in the attempt, it was nothing mote than a worthless marsh. However, to an agronomist with a robust treasury at his back, it was a bonanza. By authorization of the Pittsburgh financiers, Carmen Smith acquired the farm in January 1903 and straightway proceeded with the construction of a dike and pumping system to drain the soil. In some places the dike reached a height of 30 feet. At the same time 100 family houses were constructed together with a church and a school, and it was planned to import 100 Russian families to farm the land. Smith expected to grow four to five thousand acres of beets and he even visualized the possibility of finding coal under the surface to supply the factory. Kohns dream was to import families from the lowlands of Holland to grow cabbage and other vegetables in rotation with beets.

In February Kilbys construction engineer Johann (John) Roos, who had erected the Wallaceburg house in the previous year, took charge at Owosso and with him came his assistant, Charles L. Wagner, for the past two years chemist at Saginaw, who later made his mark in Porte Rico, Roes was a former Prussian military officer, a gentleman of culture and an engineer of parts. He was also reputed to be a discriminating judge of good Schnaps. He maintained an ice box in his private office wherein there was stored an assortment of the accessories of conviviality. These attracted Kohn and other scholarly gentlemen for an occasional invigorating pause. The big surprise came with the unexpected visit of Chief Engineer John Taylor, a rabid teetotaler, just as the boys were in the midst of a session. He gave them a severe lecture on the effect of setting a horrible example.

There was vigorous rivalry between Rcos at Owosso and George Lewis at Menominee, Roos had the advantage and was forging ahead because he had the Kilby champion rigger, Ed Coombs. In his crew he also had Shorty Frey and Skinny Tovatt, Shorty being the tallest man in the crew and Tony Tovatt the shortest. One day Ed was prowling about on the steel on the pan floor when he suffered a slip and lost his life. This was a tragedy not only in the loss of a man of superior quality and character and a pastmaster in sugar house erection, but also in that Roes lost his lead.

The construction work offered excitement as usual and attracted great crowds on Sundays. On the other hand, there was nothing spectacular about the lowly beet. The editor published dissertations on beet growing which few farmers read, or heeded if they did. In April he reported that milk was in short supply for the reason that the farmers were selling their cows and going into beet growing. This was doubtless editorial license employed to stampede the farmers into more acreage, since a properly informed farmer associates both cows and beets with permanent agriculture. The wondrous exhibition of activity at the "tremendous" factory engendered enthusiasm even in Pittsburgh, so much so that on June first the Owosso Sugar Co. acquired the Lansing factory at the "bargain" price of 60 cents on the dollar. It was stated that the factory had never made any profit and in fact lost heavily in 1901. A few days later there came the dampening news that the flood had broken through the dike at the Prairie Farm and inundated the thousandacre beet field. However, the foreman predicted no damage to the beets.

The important facts in the weekly sugar house column of the November 11th (1903) issue of the Daily Press were the arrival of chemist Lederer, the completion of the brick work, progress on the pouring of the con-crete floors and Kilbys $8,O0O payroll of the last fortnight. Two weeks later the fires were started under the boilers and the water test was begun. Joe Kohn insisted on taking a hand in every detail including the worrying. The interests of the house would have been better served if he had remained in his swivel chair and directed operation through his foremen. For testing the Wellner Jelinek evaporator, Joe himself turned on the water from the city system. While the big trunkshaped vessel was filling he became absorbed in other details. He forgot about the evaporator till the reminder came with a splash when the front end bolts sheared off.

On December 9th Captain Brown and his associates came from Pittsburgh to Owosso bringing "Tama Jim" Wilson, the famous United States Secretary of Agriculture. Facihties for entertaining consequential guests had been provided on the upper floor of the office. There was a hall through the middle with 4 bedrooms on each side and a bath at the end. The basement was equipped with a kitchen and a dining room. The Secretary made one of his happy speeches and then pulled the whistle cord to signal the opening of the campaign. Then, with Kohn and Roos in the lead, the official parade was conducted through the factory. The ceremonies were concluded with a banquet presided over by Manager Smith and Agriculturist Dolseu.

While the operators undertook the grief of breaking in the new brcncho, Joe Kohn exercised his privilege and right to operate valves at pleasure, usually omitting to confide his purpose to the foreman or station attendant.

He performed like the preoccupied housewife who intended to turn off the switch when the roast browned but, with so many things cocking at once, she forgot it. And besides, he took pride in exhibiting his operative craftsmanship. In Michigan he had to deal with independent lumber jacks who were accustomed to use their own heads while in Austria he had been surrounded with welltrained artisans who tipped their caps at his approach.

The unusual installation of the washer in a deep pit, arranged so that the flume delivered the beets directly over the top, caused inconvenience and was the first thing placed on the list for revision after the campaign. If Kohns technology had been supplemented by the pedagogic qualities of Charlie Sieland or Henry Vallez and the administrative capacity of Bill Bloodless, the record of the preliminary operation could have been covered in one sentence. Roos and the Kilby construction staff were unable to discharge their responsibilities of attaining guaranteed capacity until in some manner they had contrived to induce Kohn to absent himself by representing his urgent need at Lansing or the chemical plant.* The constructors, of course, reach mechanical capacity with greater facility in the absence of chemical control or "valve termites" When Kohn returned and found the factory operating at capacity he promptly signed Kilbys acceptance certificate.

The Christmas holidays were joyously celebrated. The factory was cutting 500 tons per shift. On December 23 Santa Claus came down the chimney in the chief engineers office. Master of Ceremonies John Doroe presented popular foreman Roy Forsyth with a meerschaum pipe, a pair of field glasses and a gold ring. Furthermore, in behalf of the Kilby pipe fitters he gave Matthew Wilson a 14kt. Pythian ring. Then Roy Forsythe, in behalf of the sugar workers, presented John with a leather chair. Everybody was happy including Kohn; and the factory was operating harmoniously.

Now it happened that S. W. "Sid" Sinsheirner of the Oxnard Construction Co. was making a tour of the Michigan factories and he arrived at the St. Louis factory early in the morning of Christmas Eve. This factory was making its first campaign and Dyers construction engineer (i.e. the chronicler) was still standing by with nothing on his mind except the preparation of the report on the behavior of the new equipment. Sinsheimer suggested accompanying him to Alma and Owosso. In the afternoon the twain presented themselves in Manager Hathaways office at the Alma factory. The purpose of the visit was obvious but Hathaway volunteered no invitation to tour the works. Finally Sinsheimer asked him if visitors would be admitted. Hathaway replied that there would be no restrictions for him, but in respect to his companion, he recalled that only recently he had been denied admittance because of his suspected "photographic eye"! Accordingly Hathaway and Sinsheimer proceeded to tour the factory while the "photographic eye" waited in the office contemplating with satisfaction that through his hobnobbing conventions with Superintendent Vance Wolfe, Engineer Bert Kilby, and especially with chemist Morrison, he had been able to send back to Dyer headquarters in Cleveland a bulky report of what he had learned at Alma. Among the craftsmen the interchange of ideas was becoming standard practice in spite of the prejudice of the untutored managers of the time who, in their great respect for secrets, as Dr. Charles Kettering puts it, "were locking more out than they were locking in."

At the conclusion of the Alma visit there was just tune to catch the Ann Arbor combination train for Owosso. A heavy snow was falling and, delayed by the snow as well as the switching at way stations, the locomotive ground to a halt at the outskirts of Owosso to wait for a snow plow. The clock indicated midnight on Christmas Eve. A mile away the bright lights marked the location of the sugar house, and accordingly the junketeers proceeded by shanks mate.

At the front door, night superintendent Roy Forsythe, formerly foreman at Essexville, bearing in mind Kohn's prescription against visitors, apologetically declined admittance. Kohn, having continued the celebration of Santa Claus arrival of the night before was presently asleep in the laboratory. Roy was disturbed lest Kohn might awaken and cause painful embarrassment in case he found visitors in the house. On the other hand, Tony Tovatt, being a rigger, was accustomed to taking risks and he declared that it was unseemly to refuse haven on a stormy night. This idea prevailed and Tony and Roy served as hosts till the guests departed at sunrise.

A preposterous story was circulated that the constructors had locked Kohn up in his quarters over the office and supplied him with epicureal luxuries until the guaranteed capacity had been achieved. Similarly in Crockett in l898, the preliminary operation had become distressed by Kohns bypassing of the station attendants. This is said to have led to a fight with master mechanic Ed Hopkins in which the decision went to Ed. Bert Kilby concluded that Kohns duty to the house had been fulfilled when the design and construction of the works was finished and accordingly he arranged an elegant. allexpense vacation for Kohn in San Francisco and thereby afforded relief to all concerned.

The campaign closed on January 26 and everybody went home. The crop had returned only 26,000 tons of beets. There was nothing to brag about but it was nevertheless a start. John Roos remained for a time in Owosso and was then reported to have joined the engineering staff of Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company.

Early in the fall it was decided that Kohn be relieved of detailed supervision in order to apply himself to the genenl direction of all of the properties. Strangely enough Sinsheimer received the appointment of the superintendency of Owosso. This may have been influenced by Joe Kilby who claimed that the factories responded more generously under the supervision of western men and he was of course concerned in the performance of his factory.

Adventitiously Sinsheimer had been released when the Oxnard Construction Company attracted no contracts in 1904. With the cooperation of Roy Forsythe and Tony Tovatt, he made certain plant revisions and started the campaign on October the twentysecond. Nervous, fidgety Kohn essayed his practice of gratuitous orders. Sinsheimer respected his useful contributions but other-wise followed his own counsel. On an occasion when there was an interruption in the flow of beets. Kohn happened to observe the battery thermometers and impulsively hollered, Shut down the battery quick. Look at die Thermometers. Youll cook the beets." Sinsheimer answered calmly, You damned fool, cant you see that the battery is shut down!"

The campaign was completed December 4. having cut 40,000 tons of beets in 43 days. During this yeat the business men of the Owosso, suburb of Corunna, in view of the discouragingly low acreage of the first campaign, had decided to make a contribution to the factory. These amateur farmers organized a beet growing association and lost $12,000 but leaned the shoemakers lesson, to stick to his last. Inasmuch as the project had been undertaken to redeem the acreage pledge which had been made to the sugar company, the village citizens proposed a bond issue to reimburse the association.

At this time Col. W. M. Wiley of the Amity Land Company and the alphabetical AKVSB & IL Company (Arkansas Valley Sugar Beet and Irrigated Land Co.), with which the Oxnard Construction Co. had been connected was promoting its pioneer factory at Holly, Colorado in the Arkansas Valley. It followed naturally that Sinsheimer, former Oxnard engineer, experienced in every phase of the industry, was selected to manage the construction and operating division from which the great Holly Sugar Corporation evolved. Then Tony Tovatts Christmas Eve hospitality paid off. He erected the Holly factory in 1905 and thereafter continued as chief erector and operator till 1926. In that year he dismantled the Huntington Beach factory and shipped it to Torrington, Wyoming. Thereafter illness prevented his transfer out of California and so he retired. To maintain the will to live he established a hardware merchandising business in Huntington Beach which in 1954 was still flourishing with old Tony Tovatt in charge and his son as partner.

Sinsheimers operation developed that the Owosso factory could cut all the beets that could be delivered, at least to the limit of Kilbys guarantee, Q.E.D. After Sinsheimers departure, mechanical operation became routine and craftsmen came and went like ships that pass in the night. Yasujuro Nikaido, the Japanese chemist, author of the informative Beet Sugar Making, was brought from Ames, Nebraska, to take charge of the laboratory. He was later transferred to the chemical plant at Bay City but was frequently called to the Prairie Fram for soil analyses and to Owosso and Lansing for unraveling chemical knots.

The annual bugbear was the disposal of the pulp. In 1907 the surplus, which the farmers had not carted away as a free gift from the sugar company, was flushed into the Shiawassee River. This was followed by a law suit instituted by the village of Chesaning and resulted in a fine of $500 in addition to a permanent injunction against dumping pulp into the river.

In 1908, Charles D. Bell, formerly superintendent of Alma, was placed in charge of the works under Kohn. This was the year of special importance for J. E. Larrowe. In co-operation with Henry Vallez and Engineer Emil Salich, he built at Owosso the first of about twenty pulp driers which started him on a great career of activity and affluence.

In 1910 Joseph Kohn suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 52. Thus ended the life of the engineer who had laid down the design of the Kilby standard sugar house. His position of general superintendent was left vacant while the superintendents of the three plants and the Prairie farm reported to General Manager Carmen Smith. In the summer of 1916 the position was revived in respect to the two sugar factories and Bell was appointed to fill it. Master Mechanic William (Bill) Dernuth was elevated to Bells old job and former assistant William H. "Shorty" Frey became master mechanic. Stone Oberg (no kin to the Grand Island Obergs), having begun his sugar career in Kilbys construction crew at Owosso in 1903, had attained the position of chief chemist.

To youthful Morell Buchele, age 17, who became attached to Stones laboratory in 1919, the most impressive thing was the great clatter that emanated from the adjoining office. This office was occupied jointly by Engineer Shorty Frey. the biggest man in the factory, and Superintendent Bill Demuth, the loudest. When these two men were in session and their vocabularies were in good operating condition, the din that accompanied the rehashing of old tales made the rafters shiver. Charlie Bell, making his nightly after- dinner inspection, used to project his head through the doorway to satisfy himself that their performance confined itself to the line of duty.

The Prairie Farm developed wondrous fertility. In 1909, 8,500 acres had been diked and equipped with a drainage pumping system. That year the farm grew a square mile of beets in addition to grass, grain, vegetables and peppermint, aggregating 3,000 acres. Cabbage, the largest crop after beets, rolled to market by the carload. Two peppermint stills were erected and returned 35,000 pounds of peppermint oil valued at $1.35 per pound. On an occasion an unsophisticated laborer mistook a sample jug of peppermint oil for drinking water. Before he sensed the difference the oil choked him and he could not be revived. The principle of "attractive nuisance" had not been promulgated and thus the company was absolved of responsibility. 160 men and 58 teams of draft horses were employed to operate the farm. Foreman Jacob DeGeus, of Belgian extraction, raised Belgian horses of noble breed. Avocationally he operated a 300 acre farm of his own, whereon, by somewhat of exaggeration, it was said that he grew affluent, while the company farm, beset by war conditions, depression and swivelchair advisers, was profitless. Both Kohn and Carmen Smith were lovers of fine horses. The farm made a convenient stopping point between Bay City and Owosso for Kohns, highstepping carriage span.

One night in February 1920 when Carmen Smith was returning from Chicago in a Pullman berth, he was suddenly stricken with a heart attack and was found dead by the porter. His managerial duties were divided between Harry Chapin at the distillery in Bay City, Bell at Owosso and Lansing and Jacob DeGeus at the Prairie Farm. Bell promoted Demnth to the position of general superintendent and placed his former Alma protege, Marshall Allen, into the berth of superintendent. Marshalls most important performance was the installation of a Steffen house in 1921. After two campaigns Allen moved to the Pennsylvania cane mill in Miami, Florida, and Stone Oberg was advanced to the supervisory job at Owosso. Stone was reputed to be equipped with an amazingly sensitive nose. One night he came running into the plant from his home a mile away and announced that he smelled carmelized sugar in the feed water, And this is said to have occurred with the wind blowing at his back! Parenthetically, Buchele, having absorbed the fundamentals by four years of association with Oberg and Allen, proceeded to make the circle of Caro, Carrollton and Sebewaing and fetched up in 1950 as superintendent at Alma.

The junior staff included assistants Bill Holzheuer, whom Bell had brought from Alma, and a homegrown lad, James Mansor, by name. Jims father had come to the plant in 1904 and worked there for 27 years till he suffered an accident that made him an invalid. Jims career began in 1908 as a laborer rated at 15 cents per hour. On one New Years night at low twelve, while Jim was in charge, some prankster tied down the whistle cord and woke up the entire neighborhood. Bell, in great wrath, called up and told Jim to pack up and get out. He was fired. Jim asked if Bells order was to take effect at once or if it should await the arrival of his relief. Bells answer was to leave the plant. A few minutes later Bell called up again and apologized for his temper. On the next pay day Jim found a raise of $25 in his envelop. In 1923 Bell made the generous concession of the 50/50 contract with the farmers.

In the spring of 1924, Captain Brown and his associates developed a desire to be relieved of the hazard of chemurgic operations. Accordingly they said sold the two sugar factories to the Michigan Sugar Company, the consideration, as reported in the public press, being $2,000,000 in cash and preferred stock certificates. The chemical plant was sold two years later but the Prairie Farm was retained by the old shareholders. Bell, who had left Alma in 1908 without the blessings of General Manager Wallace, now left Owosso under identical circumstances arid the management of the Owosso and Lansing factories was added to the duties of the Michigan staff.

Note:

(In May 1954 the chronicler received a letter written in the beautiful hand of Mrs. Carmen Smith. It exhibited

the enthusiasm and vivacity of a woman of 30. She supplied some intimate biographical matter and in conclusion

she wrote: We knew Captain Brown and family in Minneapolis and our friendship continued for years until the men

joined � that happy hunting ground - and now the wives are there also; I shall be 82 soon - and then we will all

be with our families again.)

In the reorganization, Decmuth was also dispatched. In 1925 he returned to the Kilby staff to assist Frank Burman in the enlargement of the Mt. Clemens factory, When this assignment was completed, he retired to the home of daughter Wilma in Owosso where he died about 1953.

As to Bell, he remained for a time in Owosso, being connected with a chemical plant. For a goodly number of years his name came up in the bull sessions of the craftsmen but his address was unknown.

In 1948 the chronicler, enroute from San Francisco to Los Angeles, passed through the village of Los Alamos, the location of the Bell ranch where Charlie Bell was born. Adventitiously a pair of old men of congenial demeanor were standing at the curb persuing some mirthprovoking subject. One of these, Henry Gewe by name, onetime yard master at the Betteravia factory, spoke up and said that his father, the village smith, had been the special attraction to Bell whenever he came to town even as artificers in iron had always fascinated sidewalk superintendents since the days of Hiram of Tyre.

The Bell Ranch near Los Alamos, where Charlie was raised, covered forty square miles of treeless hills which were suitable for grazing if the season was propitious. After Charlie had spent three years in the college of Chemistry at the University of California (9497) he launched into a career in the Alvarado sugar factory. Under B. H. Dyers special encouragement (and for a time also that of his daughter), progress was rapid and he achieved the chief chemists berth in 1899. E.H. then sent him for a short period of instruction to his son H.T. at Ogden to prepare hin for operating the La Grande, Oregon factory in 1900. Thereafter Charlie weighed anchor and followed the practice of the peregrinating sugar craftsmen, expending a year respectively as superintendent at Waverly, Washington: Carrollton, Michigan: then two years at Kitchener, Ontario; three years as Manager at Alma, Michigan and finally 14 years as Manager at Owosso, Michigan. When the Michigan Sugar Company acquired the Owosso factory, Charlies sugar career came to an end. He then returned to Los Alamos with the thought of trying his hand as a farmer.

The Farm had fallen upon evil days, the effect of which became felt in the home of Charlies widowed mother. In fact, Charlie, generous soul that he was, freely shared his sugar house stipend for his mothers comfort. The burden of the farm had been heavy and so he left Owosso with some obligations undertaken by generous friends. After a period of faltering at Los Alamos, it developed that there was an oil dome under Charlies barren hills. When this fact was discovered, Charlie became a millionaire overnight. One of his early acts was a friendly visit to Cwosso to reimburse his creditors and he did not quibble about adding a few extra bills for good me a sure.

The patriarchs of Los Alamos stage an annual barbecue at which there is general merrymaking and rehashing of tall tales to extol the superiority of the last generation in contrast with the present. Charlie never missed these conventions with his friend the village smith, even when the condition of his heart made attendance a hardship. On the occasion of his last participation in 1945 he approached the center of good cheer and called the dispenser attention to the fact that he was accompanied by two doctors. He therefore considered it a safe risk to join in the elbow bending just for today. In 1946 he had grown too weak to be present, and in 1947 just before the scheduled convention, he succumbed. His son Richard arranged interment at Owosso, the home of his daughter.

Below is the mausoleum (Oak Hill Cememtery - Owosso) of C.D. Bell and his wife and son John (who in 1924 drowned in Canada). Since 1924, the Owosso High School awards the 'John Bell' Cup to a senior who excells in sports.

Operation Ceases

Under the new ownership the Owosso works was placed in charge of Stone Oberg. The beet acreage, however, gradually reduced until it dropped below the minimum for profitable operation after the 1928 campaign. The plant was then shut down to wait out the depression but the usual maintenance was carried out in anticipation of a possible return of the farmers to beet growing. However, the factory remained idle till 1933. Stone Oberg, having directed the 1932 campaign at Lansing came back to prosecute the 1933 campaign in Owosso. Among the old hands who returned to help Oberg was Jim Mansor. He was placed in charge of the Steffen house. After the campaign Jim joined the local Chevrolet Sales Agency wherein he achieved the outstanding record that entitled him to membership in the "100CarClub". After the campaign, the factory was laid by as usual but the 1934 crop proved too small. This condition continued from year to year although the factory was held in readiness. Louis Rubelman who had served as chief chemist in the 1933 campaign, was retained as custodian and operator of the warehouse until 1940 when he entered the war service as previously recorded. When the war came, industrial works and the city limits were expanded while beet acreage was contacted. Even after the war, the farmers did not return to beet growing and finally it became evident that not enough farmers were interested in growing beets to support the factory. Thereafter it was declared surplus and served as a source of supply for materials and machinery to bolster up the remaining factories. This was especially advantageous during the period when the application of war priorities made these parts difficult of acquisition. In 1948 the buildings and land were sold except that 15 acres and the beet handling facilities were retained for the convenience of the neighborhood farmers who could not break away from the habit of growing an annual crop of beets. In its time Qwosso shared with Menominee the distinction of the largest factoty in the state of Michigan. It did not make its owners rich but it produced profit to the farmers and education in permanent agriculture. In the end it supplied the Michigan Sugar Company with the present Board Chairman Edward C. Bostock, former secretary of the Owosso Sugar Company and President Geoffrey Childs whose management has brought confidence into the industry since the blow it received in the depression of the 1920's.

By way of recapitulation, Owosso Sugar Company superintendents are listed as follows:

1903.....Joseph Kohn

1904.....S. W. Sinsheimer

1905.....Gustave Lederer

1906.....R.S. Bulla

1907.....Gustave Lederer

190815.....Charles D. Bell

191620.....William Demuth

192122.....Marshall Allen

192328.....Stone Oberg

192932.....Plant idle

1933......last campaign.....Stone

Oberg.

The statistics for 1906 to 1911 are recorded in the Senate Investigation, 1912, Page 28. In 1910 the factory cut 106,000 tons and produced 255,030 hundred weight of sugar. 1911 was the year of the deluge when the yield per acre was unexpectedly large. Beets accumulated everywhere in piles and in the shed and many tons turned sour and had to be carted to the fields and plowed under. The total tonnage of beets processed that year was 100,247 and the yield was 178,440 hundred weight of sugar.

The Prairie Farm, formerly a part of the Owosso Sugar Estate, was retained by Captain Brown and his associates until about 1933. At that time it was sold to a group recruited for the most part from New Yorks East side and organized as the "Sunrise Corporation," having the purpose of developing a utopian community. The Federal Government at Washington thought well of the scheme and advanced fund, for the purchase, subject to a mortgage. The ownership included about 500 tradesmen, small merchants and nondescripts from every walk of life in the ghetto. With special pride they styled themselves "Collectivists" and proceeded with enthusiasm to the fourteensquare-mile farm where they took possession of the three wellequipped villages of Pitcairnia, Alicia and Ciausdale. Pitcairnia, the capital as it were, possessed lodging facilities after the manner of barracks together with commissaries, shoe repair shop, nursery, school, bakery and other essentials implementing the purpose of the "Sunrisers."

The idea was grand but in the execution thereof it developed that there was lackhg the quality of sportsmanship which includes the disposition to cooperative effort, discipline and submission of personalities. Vulgar human qualities rose to the surface. All of the Utopians exhibited the willingness to accept the benefits but some of them refused to accept the assignments of tasks. Directly unhappiness developed and disintegration set in. By 1937 about onehalf of the original Sunrisers had deserted.

By way of a byproduct of the project it was told that a young woman of highly placed social position in Saginaw interested herself in the proposition to reclaim young boys from the contagious spots of New York and develop them into Thrifty farmers, In communion with a young man of mediocre estate and socialistic inclinations, who was paying court to her, she informed herself in the Marxian theories and proceeded to recite to her parents the defects in the present order. In fact, she established the superiority of socialism by pointing out the successful experiment undertaken right in their own midst. She acnounced her purpose of accompanying her friend in an inspection of the wonderful project. Imagine her surprise! What she saw was dirt, disorderliness and gloom. Along with her disillusionment she lost her infatuation and she cast the Marxian bible into the ash can.

Around 1940, Utopia having been given up as a failure, the United States Government foreclosed the mortgage and acquired ownership of the farm for a price somewhat in excess of the amount of the mortgage. The excess was distributed only among the Sunrisers who had remained, and the Court, to which the deserters had appealed, adjudged the Governments action to have been in accordance with law and justice.

It was rumored that the Governments plan was to establish a model experimental farm. However, the land was held to some extent as a retreat for pheasants and other game birds, while large parcels were leased for farming and thereby produced beets for the Saginaw factory. One Burton Brown, whom the neighbors classified as a "gentleman farmer," tented a square mile or so and, by favor of Providence, the absence of floods and the inflation of farm crop prices, he harvested abundantly. He credired his success to his astuteness and, instead of reserving the surplus, be "blew it" in the vernacular for automobiles and farm equipment. He practiced big stuff! There followed several lean years with flood damage during which the Michigan Sugar Company had to assume the burden of the equipment carrying charges. To eliminate the risk of loss by floods, Burton plunged into the project of rediking for which he purchased heavy machinery on the installment plan. The following year, just as he had counted a return of $60,000 from the forthcoming crop, a flood of unusual height washed out his dikes, which bad not been sufficiently compacted. Not a nickel was salvaged.

About 1945 the Government abandoned tenant farming. The farm was divided into 14 sections and sold respectively to fourteen individuals. The timeproven practice for successful operation of small farms still favored the independent, individualistic dirt farmer, especially when accompanied by propitious weather and government price supports. Ten years later the Prairie Farm was still growing beets for Saginaw.

Before the sale of the farm to the Suririsers, the overall management of the property came under the cognizance of Edward C. Bostock, Secretary of the Owosso Sugar Company. That colorful character Jacob De Geus, importer of Belgian horses, served as operating superintendent. Every year Jake staged a great festival for the delectation of the Sugar Company general staff, accompanied by much wining and dining. These occasions were always followed by requests for appropriations for more Belgian horses, more machinery, more diking and more everything.

Sixty years ago this November (Nov.29) a likeness of the Belgian stallion, Rubis, graced the cover of the BREEDER'S GAZETTE. When the GAZETTE chose a sire for this signal honor, whether he be equine, bovine, or ovine you can be sure that it was an animal who had proven his right to be there not just once or twice, but "again and again," as FDR use to say.

The cover page story was written by D.J. Kays from Ohio State and he could not resist the temptation to make a good story even better. Perhaps they should have had someone from Michigan State write it. Kays started out by suggesting that when Pervenche, Rubis' most famous daughter, first hit the ring at the Ohio State Fair as a two-year-old in 1923 the railbirds had to ask one another who this Rubis, her sire was.

In view of the fact that Pervenche had already been reserve junior champion at Michigan and Chicago the year before as a yearling...And that Rubis had sired the bulk of the registered colts at the Prairie Farm, owned by the Owosso Suger Co. at Alicia, Michigan ever since his importation in 1913...And that Owosso was a regular exhibitor at the Michigan State Fair and occasional exhibitor at Ohio and the International in Chicago where, in 1921, they won one first, two seconds, and one third--plus the fourth prize Get of Sire--on Rubis' colts, I doubt very much that Rubis was quite the unknown quantity that Kays made him out to be.

True, although he was selected as a two-year-old at the great national show in Brussels, Belgium, where he did well, he had not been shown much, if at all, in the United States, so he had no great show record of his own providing him a short cut to fame. And true, after standing at the head of the Owosso stud for almost ten years he was sold to John E. Skeoch of Coral, Michigan, who was not a prominent Belgian breeder. Kays says, "As a matter of fact, the stud career of Rubis was so disappointing and the old horse had grown so stale and second hand in his underpinning that Mr. DeGeus sold him on May 29, 1922."

Maybe. But by that time Owosso had a lot of his daughters on hand and were using his best known son, Garibaldi, quit heavily. I really doubt that Mr. DeGeus, the manager of Owosso, would have continued to use a "disappointment" heavily for almost ten years and then carry on with one of his sons. And it is true that the best known of Rubis' offspring came along when the horse himself was well along in years...but this sire was neither as unknown nor as unappreciated as the Ohio horse professor implied.

So when Professor Kays says, as he did in that article, that "this stallion was literally unknown prior to the time his famous daughter (Pervenche) arrived on the scene" (presumably, the Ohio State Fair was the "scene") I think he was overdoing this show ring drama business. I would surmise that Rubis was relatively unknown to D.J. Kays before Pervenche showed up. The story of Rubis is interesting enough in its own right, without that kind of help. Even the place that Rubis came to is interesting.

It was located in Saginaw County, Michigan. The reason it was not homesteaded, as was most of the Midwest, is that it was a huge marsh, unfit for cultivation. But this "muck land," much of it lying only three feet above the level of Saginaw Bay, was tremendously rich, serving, as it did, as the settling basin for thousands of upland acres. It was a delta that had to be won from the water, foot by foot, before it could be farmed. It was a job way beyond the tools and strenght of any homesteader.

The first efforts to make the marsh into farmland were attempted in the 1880's by three men named Camp, Brooks and Smith. They were a realtor and two lawyers...not the homestead types. The had large ditches cut through, enclosing three or four hundred acres of tillable land at a time and thus, they were able to have much of it farmed. Eventually their holdings came to about 10,000 acres of this prairie marsh. Whey they had, more or less, proven the practicality of the scheme they had problems aplenty. Spring floods, even with the ditches, would delay work and it was difficult to keep workmen on the isolated farms. Their efforts had been a partial success.

Eventually they sold out to the Saginaw Realty Company which had more financial muscle with which to push the drainage work further and place the project on a sounder financial basis (i.e., more money was available). Even so, the flooding and help problems continued, making it apparent that diking on a large scale was necessary as well as drainage if this giant marsh were to be farmed with any real success.

So, in 1903, enter a group of Pittsburgh investors who owned a controlling interest in the Owosso Sugar Company. Today, I suppose we would call it "venture capital." Attracted by the immense fertility of these marsh lands, and prepared to spend even more serious money, they went about the business of diking in a major way. The average height of the completed dikes was 17 to 18 feet, while the ditches were about twelve feet deep, with a gradient of three inches to the mile to carry off the excess water. When the entire 10,000 acres were enclosed there were 36 miles of dike and it was along the top of those dikes that roads, surfaced with stone and oil, were laid out. This, for the first time, afforded dependable communication and transport between all parts of the big farm and eliminated some of the isolation that caused employee problems. At the lowest ponit on the farm a pump house was erected housing four centribugal pumps which, in time of high water, were used day and night to lift the excess water from the canal (which at that point was big enough for small boats) and discharge it into the river. They had created "a bit of Holland in Michigan" and it worked.

Alicia village was a place that could boast a population of 300 to 350 in the summer work season and about 75 in the winter. It contained 80 yellow framed cottages, a general store, a boarding house, an assembly and/or dance hall, several large barns for stock and other buildings for machinery, wagons, and tools, a post office, and a large grain elevator and mint distillery which were situated on a spur track connecting the farm with the railroad six miles away. It was a company town, and the old photos suggest that it was as drab and dull as you might expect a company town to be.

It was said that the inhabitants of Alicia led an isolated and monotonous life, especially at flood time. I can believe that. Many of the workers were immigrants from Europe who, as soon as they had a stake of a few hundred dollars, would move on. I can also believe that. It is further said that when World War I cut off this supply of ambitious European peasants (many of them Slavs) the Sugar Company began hiring Mexicans, and were the first to do so in Michigan. Since I am believing everything else, I may as well believe that too. Alicia was located one mile from "Mosquito Road" entrance to the farm. The name tells you something too.

So after about 30 years man had "triumphed over the marsh." The seven-foot marsh grass had become fields of sugar beets, corn, peppermint, and rye and the "worthless swamp" had become "worth" $80 to $90 per acre. At least that would be the general assessment of the thing. I imaagine that conservationists, duck hunters, ecologists, and the ducks and muskrats --along with a few other creatures--might take a somewhat dimmer view fo the whole undertaking. I have never interviewed a duck, no do they leave any written record to refer to as we do, but I would expect an old retired duck from the state of Michigan to remember the triumph as a disaster and to say something like this; "Down around Saginaw, we really had a nice place once. Then these damn fools (people, I believe is what they are called) came along and for 30-odd years dug, drained, graded, made a lot of commotion, worried about going broke --whatever that means and just wrecked the place. It isn't even fit to live in now." (End of interview with the duck.)

In 1905, just two years after the Owosso Sugar Co. bought this tract of land, a man named Jacob DeGeus came to work for them. He was Holland born, trained in agriculture in that country, a good stockman and farmer, abitious and smart. He quickly advanced to the position of general manager and held that position unitl he retired in 1924. It was he who put the purebred herds and flocks on Prairie Farm; Belgian horses, Holstein-Friesian cattle, Hereford cattle, Duroc Jersey hogs and Delaine Merion Black Top sheep. This did not happen overnight. Needless to say, hundreds of horses were use, and while they were good horses they were not good enough to suit this Dutchman. So in 1913, Jacob DeGeus traveled to Belgium, seeking foundation stock for the Belgian breeding stable he wanted to establish, partly to upgrade their own work stock and partly to serve as a purebred breeding stable.

He reached Belgium at the time of the big Brussels show. His quest was to buy the best two-year-old stallion he could find and twenty mares. There were 230 two-year-old stallions at the show in Brussels that year. His choice of whole lot was a chestnut colt with some roan hairs named Rubis.

Rubis landed in fourth place in the show. (Editor's note: Several second, third, and fourth prizes were given at those big pre World War I shows in Belgium and France ...a fact that most importers conveniently "forgot" when marketing the young stallions over here.) Anyhow, Rubis was a good one and he was the choice of Mr. DeGeus. The owner shared Mr. DeGeus' opinion (that the judges had missed him) and he did not want to sell. So he bided his time, bought his twenty mares, and then returned to his negotiation on the horse. With the help of a considerable amount of money and some champagne (this is, again, according to Mr. Kays who wasn't there either) the deal was consummated and Rubis found himself on a train bound for Antwerp and was shipped to America with the twenty mares. They arrived at Alicia, Michigan in October of 1913 and a stable that was to play a prominent role in the breed for about 15 years was established.

During the early years at Owosso, Rubis shared stud duty with another horse named Sans Peur de Hamal, who was a three-time champion at the Michigan State Fair. This could be one reason Rubis wasn't compaigned...his stablemate was better. At least, better to look at.

Mr. DeGeus had some very pronounced opionions on stallion management. He said, "Our stallions worked the year around. Many times I saw surprised faces when farmers came to breed a mare, when we told them the stallions were working on the filed but we could call the one they preferred to use. Both our stallions, Sans Peur de Hamal and Rubis, were at least earning part of their living and kept in good health and breeding condition. The results of those working sires was a great satisfaction to me."

He fed the stallions clean oats and dust free hay three times a day, and a bran mess (or mash) twice a week. If they wre not as vigorous as he wished then he would add twice per day, three pounds of help seed mixed in his grain and cut the oats by the amount given in hemp see. He said, 'This is not dope, just a helpful feed. Do not give coarse dry feed to a stallion in service or let him fill up on too much water. Give the dry, course feed only at night. All kinds of dope to improve a stallion for breeding cannot take the place of work."

That is the regime that Rubis was under for his first nine years in America. And even though Owosso was campaigning their horses at some fairs, including a few state fairs and the International now and then, it wasn't a "glamor" type stable. To Jacom DeGeus the ultimate goal was better work horses for Prairie Farm, and in Michigan generally. The purebreds were a meant to that end, not an end in themselves. And it is interesting to note that while Rubis is remembred primarily as a sire of mares, he is also credited with siring many top geldings, including the champion at Ohio in 1926 and the heavyweight pulling team that was considered to be the national champions of 1927, weighing in at 1,990 and 2,010 pounds, they won the BREEDER'S GAZETTE sweepstakes harness for the "pullingest team of 1927."

It would seem to me that Rubis had served notice to American Belgian breeders that he was a sire to reckon with at the 1921 International. Owosso Sugar won second on an aged stallion by him, from his first crop of Michigan born colts in 1915, a younger son was second in the stud foal class, and two daughters stood first and third in the filly foal class...the one in third being Pervenche. So, when he was sold the following May (after serving some of Owosso's mares) I doubt that it was because he had failed them. His own son, Garibaldi, might have simply pushed his sire off the driver's seat. Most of the foals registered by Owosso in the years immediately following the sale of Rubis were by Garibaldi.

Then, in 1924, someting else happened that would call additional attention to the old chestnut horse. While in the ownership of Mr. Skoech, two daughters of Rubis registered as Manitta de Rubis and Naome de Rubis were foaled by mares belonging to Willam Brown, Howard City, Michigan. Michigan State, having fantastic success with Pervenche, might well have been looking for more Rubis daughters. I don't know how the horsemen at East Lansing got onto these foals but they found them and bought them as foals, giving them three daughters of Rubis.

In the meantime Pervenche, the college's first, last, and greatest daughter of Rubis had become the toast of the breed. Bred by Owosso, she was purchased by the Michigan school as a yearling. They promptly showed her to first and reserve junior champion at the 1922 International. The following year she came back to be junior and grand champion and then in 1924 she made it three in a row...senior and grand champion mare. With Jack Carter fitting and showing her she went undefeated in class those three years.

Whether this was a case of cause and effect I don't know...all I know is that in the spring of 1925 the Owosso Sugar Company bought the old horse back. By then he was 14 years old. Maybe there was another Pervenche in his loins. It was worth a chance. Promptly bred back to Qunea, the mother of Pervenche, they came very close. In 1926 she foaled Syncopaton, full sister to Pervenche, and she did go on to become another winner at Chicago. Together, she and Pervenche, would win the Produce of Cam class at the International in what proved to be Owosso's last appearence at the Chicago show. Let's talk about those 1926 and 27 Chicago shows right now. The '27 show was Rubis' finest hour.

In 1926 Michigan State showed Manitta de Rubis to first prize 2-year-old and junior champion mare. Owosso (remember they had brought the old horse back in time to use him the previous year) stood second in the filly foal class with Syncopation, full sister to Pervenche, and the second and fifth in the stud foal class with sons of Rubis. The "Gets" of Rubis and Garibaldi stood second and third for Owosso to the Ergot "Get" shown by C.E. Jones, Livermore, Iowa. That was just the warm-up for 1927...when it all came together for the old chestnut horse out on those reclaimed marshes in Michigan.

Chicago 1927 ... and seldom has one sire ever so completely dominated the Belgian mare classes. Aged mares... Pervenche, under Michigan State's colors, champion in 1923 and 24 comes back to win her fourth blue at Chicago, then goes on to reserve senior and reserve grand champion. four-year-olds...Albine Farceur, a granddaughter of Rubis (through his son Garibaldi) wins second for Owosso Sugar. Three-year-olds...Manitta de Rubis and Naome de Rubis stand first and second for Michigan State, the Manitta goes on to be senior and grand champion. Yearlings...Syncopation, full sister to Pervenche, wins the class for Owosso and goes on to junior champion. Five classes had been shown. Daughters of Rubis had won three of them and claimed one second, a granddaughter had picked up another second. Foals...Ravenche, a daughter of Pervenche, wins the class for Michigan State, Owosso is in third with a daughter of Rubis. The Rubis daughters claim five of the six purples for Belgian mares. Then Michigan State wins Best Three Mares and Get of Sire on pervenche, Manitta, and Naome. Owosso borrows back the mare they bred, Pervenche, puts her with her yearling full sister and wins the Produce of Dam. No wonder Rubis rated the cover of the November 1929 BREEDER'S GAZETTE.

I suppose you might expect that this was the beginning of a great dynasty of horses at Michigan State, built on these magnificent mares. That didn't happen, at least, not quite that way. The International was always a market as well as a show. A lot of horses changed hands in Chicago, and the horsemen at East Lansing were business men as well as showmen. They had to "cash their dividends" once in awhile and with victories like that it was market day.

On December 1, 1927 (which would have been during International week) all three of the great Rubis daughters belonging to Michigan State were sold; Pervenche to Earle Brown, Brooklyn Farm, Minneapolis, Minnesota and Manitta and Naome to G.N. Dayton, of department store fame and also from the Twin Cities. The Daytons were laying the foundation for their famous Boulder Bridge Farm stable at Excelsior, Minnesota and they did it with Rubis and Farceur bred horses, the very best money could buy. The following February they also obtained Syncopation, putting the four Rubis daughters that had brought national fame to the old horse, all in the state of Minnesota.

Pervenche was repurchased by the college from Brown in 1932 and ended her days on the East Lansing campus, where she did found something of a dynasty. She was our featured brood mare in the Winter 1975 issue of the DHJ. In that article Jack Caarter, long-time horseman at Michigan State, is quoted as follows: "Pervenche was the complete draft horse. There wasn't a mare like her and there hasn't been one since. She was a great bodied mare with great muscling. On the top she couldn't be faulted. She had the best feet, legs, and ankles I ever saw on a mare and she could move just like a machine. She was a grand mare! When she came back from Browns she wasn't quite the same mare. She had had rough use in the hitches up there at Browns. Her feet and legs were all banged up from being use in the hitches so much."

Under the capable management of Les Wilson, the Rubis daughters wasted no time in putting the new stable known as Boulder Bridge into the front row of Belgian breeders and exhibitors. The three daughters won the "Get" class for their sire at the 1928 and 29 National Shows in Waterloo. Manitta was first prize 4-year-old in Chicago for them in 1928 and grand at Illinois the following year. Naome was first prize four-year-old at the National in 1929 and continued to tramp on in the show herd for four more years, rarely winning the championship but always challenging. Syncopation was grand at Iowa and reserve junior at Chicago for Boulder Bridge in '28, won the three-year-old class at Illinois in '29 and the four-year-old class at Minnesota and Waterloo in 1930.

Naome produced a son, Boulder Bridge Naomarq, by Marquis de Faceur, that was a consistent winner and was used extensively at Boulder Bridge. Manitta produced three daughters by three different sires that were all consistent winners at the major shows. They were Boulder Bridge Manet (by Marquis de Faceur), Boulder Bridge Victoria (by Victor de Bois), and Boulder Bridge Mirza (by Gerfaut Ophain). Needless to say, Boulder Bridge won the Produce of Dam class with hose girls more than a few times. So the Rubis daughters did breed on, both at Michigan State and Boulder Bridge.

I'm not going to pursue this bloodline any further, for it was along time ago, but you can rest assured that "Rubis lives on" in ose of today's Belgian horses. I felt his story was worth retelling for a couple of reasons. First, to convince today's young Belgian breeders that "in the beginning" there was more to it than Farceur, Elegant du Marais, and Conqueror. Second, to point out that recognition doesn't always come quickly to a good sire. And third, that if you wish to have a reputation it helps to live a long time and to keep on breeding right up to the end... just like Rubis. And that, in turn, gets us back to the old horse himself. I think we left him, back in the possession of the Owosso Sugar Company for the second time, at the age of 14 in 1925. That was the year he sired Syncopation.

The 20's and 30's were not good years for Owosso's Prairie Farm. The 20's were not good for agriculture generally. As the big farm experienced more and more problems the registered Belgian herd became expendable. Their last appearance at Chicago was in '27, the followingyear most of the Belgians were transferred to Pitcairn Bros. from Alicia. I don't know what sort of arrangement this was because Alicia was the company town and there was a Pitcaairn station, or some such thing on the big farm. It might have been sort of an "in house" arrangement, or they may have been renting ground from the company. Make your own guess. In any event, Rubis --along with several of the other--was transferred to Pitcairn Bros., Alicia, Michigan in 1928. He was later leased to Michigan State and finally, in April of 1933, at 22 years of age, he was officially transferred to the college. His daughter, Pervenche, had again found a home at Michigan State and it was here, at East Lansing, that he would serve the balance of his life, breeding mares up until two weeks before his death at the age of 24.

Dan Creyts, East Lansing, Michigan loaned me a centennial book of Albee Township wich has served as my chief reference on the Owosso Sugar Company's Prairie Farm. It states, concerning the declining fortunes of the big farm in the late 20's that "selling the horses didn't help and matters got worse." (Now that can be said of a lot smaller farms in the country too!) Anyhow, a plan to sell the remaining livestock and equipment and lease the land to neighboring farmers on a crop share basis was put into effect. According to this bookof Dan's taxes had gone unpaid for as long as four years...it really was a mess.

It was about that time (1928-30) that the rest of the country was invited to the depression that the farmers had been experiencing for some time. That didn't make things better either and in 1933 the leasing plan was scrapped and the Big Prairie Farm changed hands again. And what a change it was.

The leader of the group that bought Prairie Farm was Joseph J. Cohen, a Russian born Jewish Rabbi, who was active in socialist reform groups. He envisioned, for Prairie Farm, a "collectivist society, a free organization uninhibited by demands of any manmade rule." Wow! no manmade rules.

In spite of the record of failure of many such rural utopias in our own brief history, he got the diking cranked up and the resulting Sunrise Cooperative Farm Community on the old Big Prairie Farm in Michigan was one of the last of its kind in many years. He had some unconventional ideas but it was 1933, half the country was out of work, and any message was better than despair. Each family contributed $1,000, the farm was bought, and new shareholders poured into Alicia. There was one big problem. Hardly any of them know how to farm. Cohen solved that by hiring former workers on the Prairie farm and coaxing Jacob DeGeus out of retirement to serve as advisor.

Things did not go well. In the second year 14 of the families packed up and left. The first "deserters" were just that, the first, they were followed by others. But the ones who left weren't the only problem, as Dan's centennial book states, there were some that stayed and didn't want to leave such as "individualists like 'Preacher Hyman,' who thought the Sunset Community would benefit from his won doctrine, and the lazy guitar player, who refused to do his share of work, were continually creating difficulties and raising complaints from their fellow workers."

In the meantime, the Sunrise Commuiity had entered into an arrangement with the Farm Security Administration in 1936, whereby the Sunrise Community people would be given first pick of the land to farm cooperatively, but the land was owned by the government. The price was $270,629 for the whle parcel and it was now Uncle Sam's. This didn't work either. Twenty-five families hung on for two years and then left. Utopia simply didn't work, even with the government as the landlord.

From 1938 up until World War II called more land into production, the big Prairie Farm was used only sporadically and piecemeal. During the war, of course, more of it was rented out but the eight years of government ownership were basically "years of neglect and deterioration. Buildings became dilapidated, canals broke up and dikes grew in need of repair."

On March 1, 1945, as the war was in its final years, the federal government got out of owning Prairie Farm by selling it to a group of local farmers for $265,000, slightly less than they had paid the utopians in 1936. Fourteen farmers then proceeded to go their seperate ways. The big Prairie Farm, as such, finally lost its identity.

And that is all I'm going to tell you about Rubis, the Owosso Sugar Company, Jacob DeGeus, the the Big Prairie Farm. I'm indebted to Dan Creyts, East Lansing, Michigan and Jim Richendollar, Belleville, Michigan for providing information of this story.

AN ADDENDUM TO "RUBIS"

The reputation of Rubis hinged, to a great extent, on four daughters--all dealt with in the previous article. That was his "national reputation." But the state of Michigan where he sired colts, non-stop, for twenty-two years you can be sure that a lot of sons had "local reputations." His imorter, Jacob DeGeus as interested in "improving the work stock of Michigan" and you can be sure that Rubis made a mighty, if largely unknown, contribution in that respect.

Here is a little something that Bob Duton, Saranac, Michigan recalls about a Rubis son in his community:

"Undoubtedly many sons of Rubis were 'traveling men,' not in the sense of Constable, who served mares at one

location for a short time and then moved on, but ones who traveld to several different farms in the same

community...day after day, year after year."

"One such son was Major De Rubis, a strawberry roan with silver mane and tail. He was owned by Alford Wheelock (Fred) of Saranac, Michigan. This stocky built roan (most of them were stocky built) weighing 2000-2100 pounds was purchased as a four-year-old in 1929 from a man in Grand Ledge. Rube began stud duty immediately and continued for 20 years. Unlike some studs who walked from farm to farm, Rube traveled in style--in the early 30's he rode in a model T Ford truck and then later on in a model A. This allowed Rube to cover a 20-mile radius around Saranac. He would breed from two to four mares a day at the height of the season and serviced 100 to 110 mares during the season which started in March and ended in July. Obviously, not every stop resulted in a service. Some farmers were confident their mare was in season but Rube knew differently. He grew to be cagey and was rarely kicked.

This gentle son of Rubis was broke but didn't work too much, especially during the breeding season. He did do odd jobs around the Wheelock place, like pulling a stone boat along when stones were picked from a field. Like many of the horses of that day Rube was an easy keeper, getting corn, oats and some wheat and linseed meal.

"Breeding contracts at that time were mostly oral, nothing written. Rube's fee for a live foal was $15. Mr Wheelock would send post cards to his customers about foaling time, reminding them of their stud fee obligation. And though this was during the depression times, the farmers rarely failed to pay. Since there were few registered mares at the time, most of Rube's offsspring were grades. And most of them were roans.

"Mr. Wheelock's house burned down in 1947 and any pictures of Rube were lost. Then Mr. Wheelock died in 1951. Two sons, Leo and Joe, remember the stallion business well. Joe, now 82, sometimes traveled Rube but Joe, being 12 years younger, was too young to take him on the road at the time." --Bob Duton, Saranac, Michigan

In visiting with Dan Creyts about the Owosso Sugar Co. Prairie Farm he said on of the old employees of the place, when it was in its heyday, recalled that there were 27 miles of canals to ice skate on in the wintertime. He provided much of the background material.

The old Owosso Sugar Factory as it looked in 2003.

More Shiawassee County History

Last Update: 1-09-24......

This is a personal website owned by Steve Schmidt.

Copying any photos and information is prohibited.

Copyright 2024 © All rights reserved